Tungsten carbide seal faces are known for their excellent dureté et résistance à l'usure.

They are used in pumps, mixers, and compressors across industries such as chemical processing, pétrole et gaz, and water treatment.

Despite their toughness, these seal faces are not immune to all forms of damage.

One issue that quietly develops in some applications is leaching—a chemical attack that removes the metallic binder from the carbide structure.

Leaching can weaken the seal surface, increase leakage, and cause early failure.

This article explains the causes, symptoms, and prevention of leaching, using real-world examples to help plant managers and engineers identify and mitigate it effectively.

What Is Leaching?

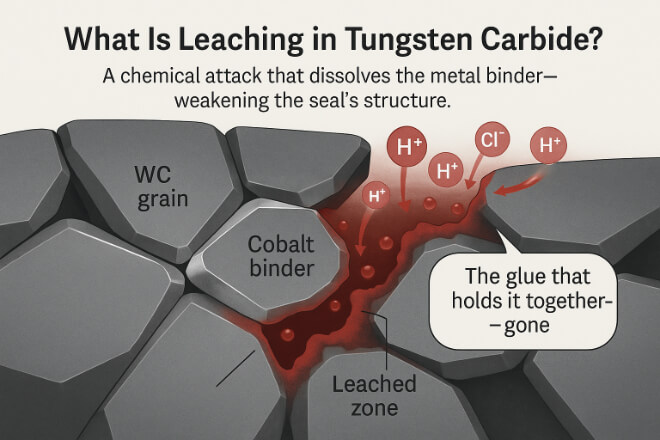

Tungsten carbide is a composite material. It consists of hard WC (tungsten carbide) grains bonded together with a softer metal binder—usually cobalt or nickel. The binder gives dureté and holds the structure together.

Leaching happens when the binder is chemically dissolved by the process fluid.

The tungsten carbide grains remain, but without binder support, they become loose, and the surface becomes porous and weak.

A simple way to imagine it: think of the binder as the “glue” between bricks. If the glue dissolves, the wall is still standing—but fragile and ready to crumble.

Leaching is not caused by friction like normal wear. It is chemical corrosion, often accelerated by temperature, fluid chemistry, and electrochemical effects.

Real-World Example: Chemical Pump in Acidic Service

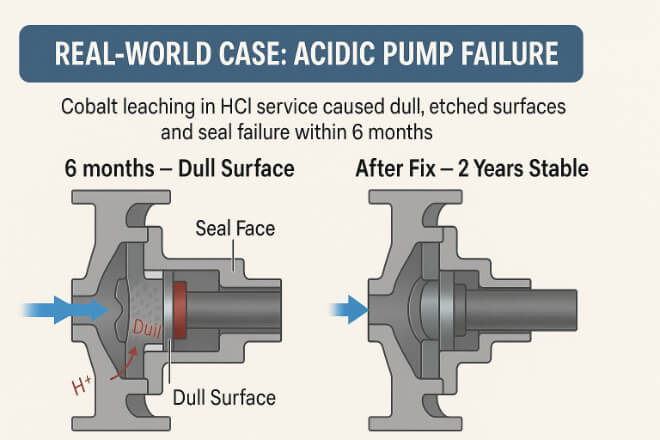

In one petrochemical plant, a pump handling dilute hydrochloric acid showed premature seal failure after only six months.

When the seal faces were inspected, engineers noticed dull, etched surfaces and micro-pitting under a microscope. Chemical analysis of the flush fluid showed traces of cobalt ions.

The investigation confirmed binder leaching. The cobalt in the tungsten carbide face had dissolved in the acidic environment.

The problem was solved by switching to a nickel-bonded tungsten carbide grade and adding a thin protective coating.

After the change, the seals lasted over two years without similar damage.

Causes of Leaching

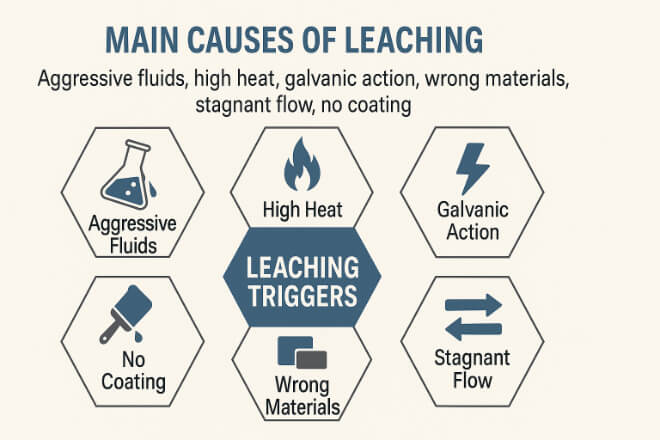

1). Aggressive Fluids

Fluids with strong acids, alkalis, or high chloride content can attack the binder metal.

Example:

Seawater pumps often suffer leaching because chlorides aggressively dissolve cobalt.

In paper mills, alkaline white water can attack carbide binders over time.

2). High Temperature

Higher temperatures increase the reaction rate. If a seal face overheats due to poor cooling or dry running, the leaching process speeds up.

Example:

In refinery pumps running at 180°C, cobalt leaching is often observed near the hottest contact zones, especially when flush flow is restricted.

3). Electrochemical Action

If dissimilar metals are in contact through a conductive fluid, galvanic corrosion can occur. The cobalt binder may become the “anode” and dissolve.

Example:

A pump with stainless steel housing and tungsten carbide faces experienced leaching due to stray current and galvanic potential. Isolating the seal electrically solved the issue.

4). Unsuitable Material Grade

Grades with high cobalt content are tougher but less résistant à la corrosion. Using them in acidic or chloride-rich fluids invites trouble.

Example:

A food-processing plant using cobalt-bonded tungsten carbide in a cleaning solution with chlorine reported frequent seal dulling. After switching to binderless carbide, the issue disappeared.

5). Stagnant or Low Flow Zones

If the flush flow is poor, aggressive fluid remains near the seal face longer, increasing attack time.

Good flow acts like self-cleaning; poor flow makes local chemistry more concentrated and damaging.

6). Lack of Protective Coatings

A thin coating like DLC (diamond-like carbon) or chromium nitride can block chemical access to the binder.

Without such protection, even mild corrosive fluids can slowly leach the surface.

Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

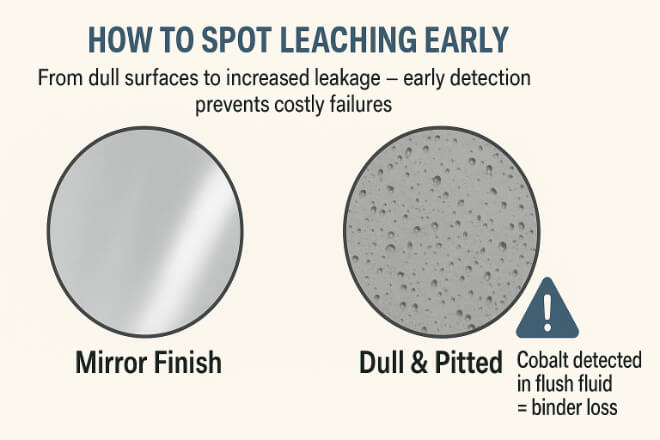

Spotting leaching early can prevent expensive shutdowns. Here’s what to look for:

Dull or Matt Surface

Polished tungsten carbide should look mirror-like. When leaching begins, the surface becomes dull, often near the fluid edge.

Fine Pitting

Tiny pits or rough patches may appear under magnification. These are places where binder has been removed.

Increased Leakage

Once the surface loses flatness, leakage rises even under normal pressure.

Temperature Increase

A rougher surface increases friction, generating more heat—often a warning sign before visible wear appears.

Surface Flaking

In advanced cases, the outer layer weakens and small flakes break off, exposing fresh carbide to attack.

Changes in Fluid Composition

Finding cobalt or nickel ions in the flush or process fluid is direct evidence of binder leaching.

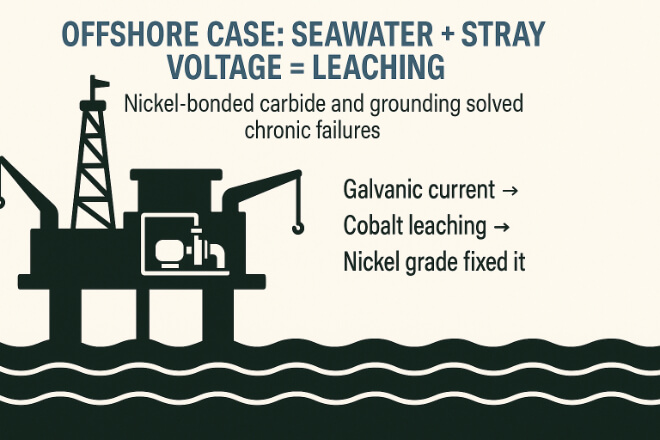

Example: Water Injection Pump in Offshore Platform

A water injection pump on an offshore oil platform suffered repeated mechanical seal failures.

The seawater service, combined with occasional voltage potential between pump casing and motor frame, created electrochemical leaching of the cobalt binder.

When engineers replaced the seal faces with nickel-bonded tungsten carbide and ensured proper grounding, the problem was eliminated.

The new seals operated for more than three years without visible leaching.

How Leaching Affects Operations

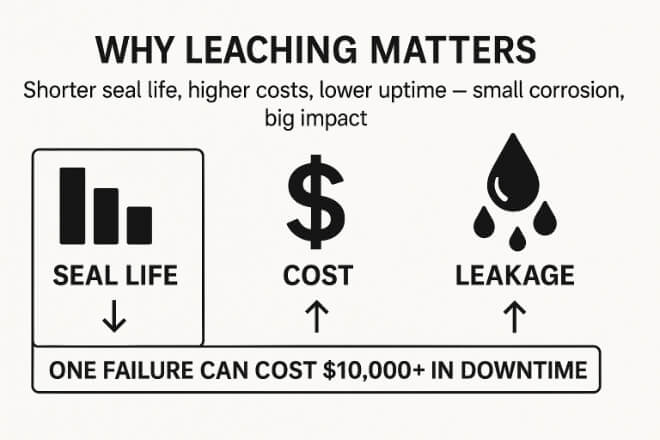

For decision-makers, leaching is not just a material issue—it impacts the entire operation:

Shortened seal life increases replacement cost.

Unexpected shutdowns reduce equipment availability.

Leakage and contamination can compromise product quality or safety.

Higher power consumption results from increased friction.

Each premature failure also adds indirect costs such as labor, downtime, and lost production.

For large rotating equipment, preventing one seal failure can save tens of thousands of dollars.

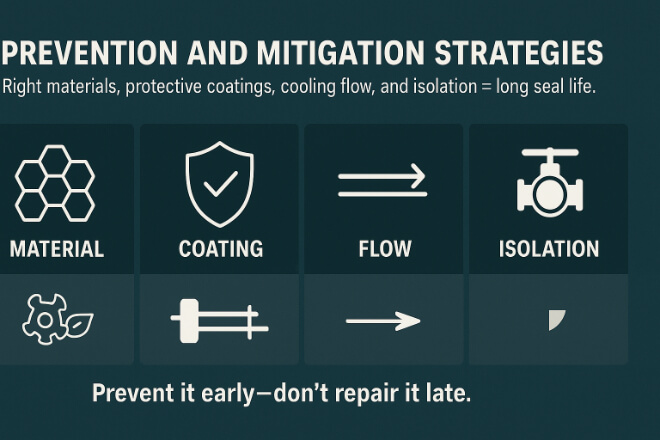

How to Prevent and Mitigate Leaching

1). Choose the Right Material

Select a grade that matches the fluid chemistry:

Nickel-bonded tungsten carbide for acidic or chloride-rich environments.

Cobalt-bonded for neutral, clean fluids where dureté matters.

Binderless carbide for extremely aggressive fluids (though more brittle).

2). Apply a Protective Coating

Use thin films like:

DLC (carbone de type diamant)

CrN (nitrure de chrome)

TiN (nitrure de titane)

These layers act as barriers and resist both corrosion and wear.

Example:

In fertilizer plants, adding a DLC coating to seal faces increased average life by 40%.

3). Control Temperature and Flow

Ensure proper flushing or cooling. Install a clean flush line if process fluid is corrosive or contains solids. Avoid long idle periods with stagnant fluid on the seal.

4). Improve Fluid Quality

Use inhibitors or filtration to remove ions and particulates that promote corrosion. Keep pH close to neutral when possible.

5). Electrical Isolation

Use insulating sleeves or grounding brushes to prevent galvanic current paths between rotating and stationary parts.

6). Scheduled Inspection

Regular inspection under a microscope can catch leaching early. Even small dull zones should prompt maintenance before they worsen.

Summary Table: Symptoms and Remedies

| Observed Symptom | Recommended Action | Dull surface finish | Switch to nickel-bonded or coated grade | Micro-pitting | Improve flush flow, reduce chemical concentration | Increased leakage | Re-lap surface, apply barrier layer coating | Flaking or chipping | Replace face, check temperature and load balance | High temperature zone on face | Enhance cooling, verify alignment and pressure |

|---|

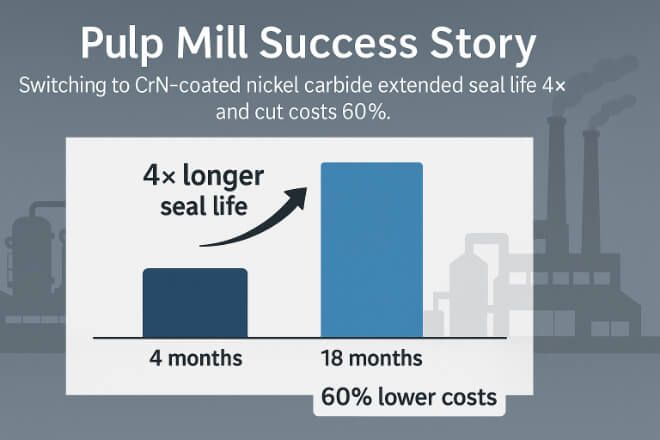

Example: Pulp Mill Seal Upgrade

A pulp mill’s pumps handling alkaline white water were suffering seal failures every four months.

Post-failure inspection revealed cobalt leaching with shallow pits and dull rings.

By changing to nickel-bonded tungsten carbide with a CrN coating, and improving the seal flush with a clean water loop, seal life was extended to 18 months.

Maintenance costs dropped by 60%, and leakage issues were resolved.

Key Takeaways for Decision Makers

Leaching is a chemical corrosion problem, not just wear.

The main triggers are aggressive fluids, high heat, and poor material selection.

Early visual signs can save major repair costs if detected on time.

Proper material, coating, and flush design can prevent leaching completely.

Investing in prevention often saves much more than the cost of replacement parts.

Conclusion

Leaching may not look dramatic at first, but once it starts, it steadily undermines seal reliability.

With proper understanding, this problem can be eliminated through smart material selection, controlled operating conditions, and consistent monitoring.

In short:

Prevent leaching early—don’t repair it late. A few material and design upgrades today can save hundreds of maintenance hours tomorrow.

Si vous souhaitez en savoir plus sur une entreprise, n'hésitez pas à Contactez-nous.